|

|

|

Duke-out in Detroit

Imagine Ford and Chevy, side by side, throttles wide open. This ain't

fiction.

By PATRICK BEDARD

Photos by AARON KILEY

Whozzat huff-and-puffer with the electric hair? You know, the guy who matches up fighters in those hyped-to-heaven slugfests. Yeah, that's him—Don King.

Well, we've out-Don King'd the man himself on this one, ginned up a face-off that makes the Thrilla in Manila seem like 14 rounds of patty-cake. Forget Marquess of Queensberry rules. We're going back to bare knuckles. Such a free-for-all, in the car culture, is called "run whutcha brung." No tech inspections, no EPA sniffers, no excuses. Just unload 'em and let it happen. This is about bragging rights, and corporate honor. Get ready for the Duke-out in Detroit!

It's FORD vs. CHEVY.

Somebody's gonna get an ear bitten off before this thing is over.

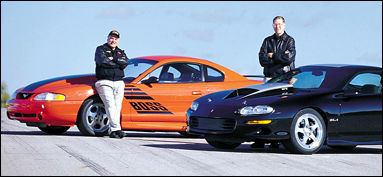

In the challenger's corner, holding the towel for the Mustang, and representing the bazillion stockholders of the Ford Motor Company, is John "The Quip" Coletti. "If he wins," he says of his GM opponent, "that Camaro is a helluva car, 'cause it's gonna take a helluva car to beat this Mustang."

The Camaro is the undisputed champ going into this bout, having bested

the Mustang the last six times they've met on our pages. (Of course, those

were production cars, and these are one-off fighting machines.) Defending

that record, and standing as the Camaro's second in this match, is Jon

"The Tower" Moss. At six foot seven, he doesn't have to raise his voice

to be noticed.

This particular rivalry flamed up five years ago. Moss was manager of Chevrolet Special Vehicles, the department that builds the ooh-and-aah models for shows and other venues that keep the public whipped up about cars. No longer was a big-block V-8 being offered in the Camaro, but to keep the threat alive, Moss's crew had implanted an all-aluminum ZL-1 race motor into a slightly used 1993 model; actually, it was the company car Moss had been using as a commuter.

In bad-boy black, the ZL-1 Camaro was a snarling overdog, just right for bump-starting a buzz at the annual Las Vegas show put on by the go-fast parts industry. Coletti was there, checking out the enemy arsenal, when a Chevy man, noticing the Ford logo on his shirt, leaned close to Coletti and said, "I bet you haven't got anything in Dearborn that can tangle with this."

Russia's Khrushchev used to run his mouth like that, too, and it kicked the Cold War into overdrive, lasting another 35 years until his side went bankrupt trying to keep up with the West.

Did Chevyman know he was baiting Ford's war department? Coletti heads Special Vehicle Engineering (SVE), which creates niche-market, muscled-up models such as the SVT Contour and the supercharged SVT F-150 Lightning pickup with one hand, and with the other cooks up the one-off show cars that compete with Jon Moss's projects for the public eye.

Coletti and Moss were, and are, generals in opposing armies. Not that

Coletti's first thought was bankrupting GM. Car guys who came of age during

the muscle-car showdowns of the '60s, as he did, have a different reflex.

He'd settle for a public humiliation; send that overdog Camaro home with

its tail between its legs.

One big problem, though. Chevyman had guessed right; Dearborn didn't have anything that could tango with the steroid-injected Camaro.

Still, if Moss could revive a '60s icon—the ZL-1 Camaro first appeared in 1969, strutting an aluminum-block 427—so could Coletti. Way back then, Ford answered Chrysler's 426 Hemi with a 429-cube semi-Hemi of its own; it had an angled-valve layout very similar to the Mopar's, with long exhaust rockers and ports like laundry chutes. Ford stuffed the broad-shouldered V-8 into just enough Mustangs (to make room, the front track had to be stretched wide) in 1969 and 1970 to meet NASCAR's homologation requirement. Boss 429 it was called, the overdog of its day. Hmm, Coletti schemed, why not build a brand-new Boss 429 and sic it on that Camaro?

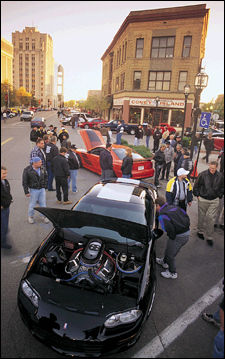

Fast forward to October 1999. After several years of provocation from Coletti and "maybes" from Moss, the match is finally on. It'll go two rounds: one on a drag strip, one on a road course. These are street cars, at least in concept, so they'll wear what look like mufflers, and we'll pretend they're quiet enough. Racing gasoline will be the fuel. As for tires: whatever fits within the stock-appearing body contours.

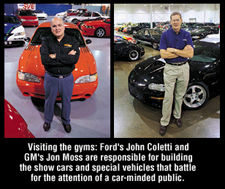

On the day before round one, we visit the fighters in their respective

gyms. Jon Moss has been promoted; now he's manager of a combined Special

Vehicles operation for all GM divisions. He, the ZL-1 Camaro, and at least

100 other remarkable cars, await us in a well-lighted industrial building

not far from GM's Tech Center in Warren, Michigan.

We see the Olds Recon, a concept sport-ute new for last season's Detroit auto show. We see the Astro II and the Astro-Vette, concept Corvettes from 1968 and 1978. We see the Buick Riviera convertible that paced the 1983 Indy 500 and the 1949 Olds convert that paced the same race 50 years ago. While Moss shows us the Chevy van built for Tim Allen's Tool Time TV show, a mechanic in a far-off service bay lights off the overdog. It fills the cavernous building with thunder—fierce combustion pulses hammering their way down exhaust pipes the size of rain gutters—and with the heavy rattle of a three-disc clutch lightened of all damping springs. It's a pagan noise, the racket of a machine that doesn't care what anyone thinks.

Moss, now 58, is an old-time engineer from the days when the technical

culture demanded that you check your emotions at the door on the way in.

Do the math, do the testing, and the truth will be revealed. But let your

peers see that you'd fallen in love with something, a design or a mechanism,

and they'd doubt your judgment forevermore. Now he's congenial to a point,

like a poker player.

The Camaro wears a fresh suit of 1999 front sheetmetal. Its engine has four huge intake throats open to the hood scoop, a new arrangement since the last public showing. He explains that the old system backfired one day and blew apart the dual-plenum intake we'd been expecting.

On the shiny side of the hood, painted on both sides of the scoop, are the numbers "572." That's cubic inches, he says. We leave the building thinking this Camaro should be "on the table" next time the world superpowers hold strategic arms reduction talks.

Across town in Dearborn, SVE holes up in an old Montgomery Ward warehouse. We arrive early. Coletti, a sparky 50-year-old, says he's not, uh, dressed for the meeting. He ducks out, and returns in a black shirt with glowing orange embroidery. "The Boss is back!" it shouts.

He leads us out to the shop, to an enclosure created by curtains hung to block our view of the prototypes beyond. Circled in the cold fluorescent light is a handful of SVE exotica, among them the smoothly chiseled V-12 mid-engined coupe that posed for our January 1995 cover; the bright-red "two-seat Indy car for the street," curiously named Indigo; a supercharged dual-fuel Mustang called the Super Stallion; and, of course, the Boss. It's an orangy red, with punchy black graphics and a huge "BOSS" on its flanks.

"I got Larry Shinoda to do the look," Coletti says. The late Larry Shinoda; this must have been one of his last design jobs. "He did the original Boss 429. It was only right that he help bring back the new one."

Somebody lifts the hood. Yep, it's baack. Even the Chrysler Hemi faithful will concede that the Boss 429 is a sexy hunk, with valve covers contoured like Mr. America's abs. This one has a single-plenum intake the size of a hay bale, fed by a mirror-polished duct curving toward a cold-air inlet in the right fender. Although the heads are Boss 429, the alloy block is a pure racing piece. "A mountain motor," Coletti says, enjoying the thought of a displacement pushing 10 liters (598 cubic inches). "Over 850 horsepower on the last dyno run, 794 pound-feet.

"This is destiny," he says. "This is all the Mustang fans across the country vs. all the Camaro fans. We're coming to the party with a lotta bullets."

Round One, Milan International Dragway: At the 9 a.m. opening bell, the Boss is wearing Firestone slicks. Two mechanics are inflating an air spring in the right rear suspension, to offset the live-axle torque reaction that tries to lift that wheel off the ground at launch.

Where's the Camaro? "Transporter's stuck in traffic," says Moss, folding his phone, obviously embarrassed.

"We give the professor 15 minutes," quips Coletti. "You get 20. Then it's a default."

Factory drivers will dial in each car, then our man Don Schroeder will make the official runs. SVE engineer Al Oslapas cranks up the Boss as the Camaro transporter rolls in, with "RELIABLE" written in six-foot letters on the semi's trailer. Moss is relieved. He starts the banter that inevitably precedes a big match.

"We're gonna lose today. Track's too cold for a stick to hook up," he says, playing up the Boss's automatic.

"I heard that five on the hood is really a six," counters the Quip, "672, zat right?"

A track worker pours a sticky liquid—the "glue" in drag-racing lingo—in the burnout area—called the "box"—then washes it around with water from a hose. Oslapas eases the Boss's slicks into the puddle and blurs 'em, roiling out a swirling cumulus of smoke. After two exploratory passes, he stays on the gas through the eyes for an 11.17-second elapsed time at 127.59 mph.

The Ford camp expected more, a lot more, and they go into a huddle as Chevy pilot Kurt Urban works with the five-speed Camaro. His first pass is an 11.05 at 131.45 mph. But the engine misfires on the next run, and drops 6 mph.

From the pits, we hear the Boss wasn't getting full throttle: "carpet balled up under the gas pedal." And the Camaro has closed the gap on two spark plugs: "weren't indexed right so the pistons whacked 'em."

They keep trying, both teams sure they have another 10 mph in the bag. But they can't find it.

Schroeder takes over the Boss. In a few runs, he works it down to 11.02 at 128.08 mph. Then he hits the rev limiter in second and comes back on seven cylinders.

Urban, an experienced drag racer, is quick with the stick; the factory guys are polite, but they can't hide their doubts about Schroeder, a mere magazine guy. Urban rides shotgun for the first few passes, acting as tutor. Then Don, on his first solo sortie, lays down an 11.06 at 127.61 mph.

"Ow, the dude can drive!"

But the times don't drop much; 11.01 at 128.64 mph is as good as the Camaro gets.

Meantime, we hear that the Boss is wounded. The cup end of an exhaust

pushrod has shattered, leaving the stub free to do a million jabs at the

billet rocker arm. The Camaro leads now by the slimmest of margins, 0.01

second. The Ford crew is working four cell phones—"Anybody have a 1.7 exhaust

rocker for a Boss 9?"

Despite its great looks, great specs, too, the big Boss V-8 was dropped

off at the orphanage years ago, abandoned by a Ford mystified by its weak

performance. When it didn't respond to early tweaks, the company turned

to other engines. Now it's a glorious antique, famous mostly for the threat

posed but never delivered. And there's a cruel truth about motors that

never earned a following—nobody has parts.

Chip Minich, Coletti's main engine mother, lights out for Dearborn hoping to scare up a fix. We agree to keep the round open for the rest of the day.

Meanwhile, Urban has reversed the slicks on the Camaro so the feathered edges dig into the track; kinda like petting the dog backward. He runs a 10.69 at 129.49, then frags the diff.

"That motor is precious to me," Coletti says, admitting a heavy emotional investment in the Boss's comeback. But now his fighter is down, and the ref is counting. Moss strides up holding out a cell phone at arm's length. Coletti puts it to his ear for about three seconds, then says sarcastically, "Susan, really great of you to call." It's Mrs. Moss, twisting the knife a little.

Just after 4 p.m., somebody's phone rings. The rocker arm has been rehabbed, and a rare set of pushrods is on the way from an obscure shop 100 miles away.

At 7 o'clock, the sun slides below the horizon, taking with it all traces of Indian-summer warmth. Emergency surgery continues on the Boss under droplights. Some of the broken parts are still missing.

A few minutes past eight, the patient awakes from the anesthetic, cold but alive. Oslapas rumbles off into the darkness, warming the engine, looking for trouble. After a half-hour, with periodic revisits to the surgeons, he makes a partial run.

"Too dark at the far end," he reports. "Can we get some cars with headlights shining on the track?" To Schroeder he says, "Do a couple easy ones. Track's slippery. It's gettin' loose on every shift."

Our man backs the booming, convulsing Ford into the glue, locks the front brakes, and does the granddaddy of all burnouts, filling the cold night with the smell of sacrificial rubber. The red coupe lunges forward, slicks squalling over the blasting exhaust—lunge, LUNGE, LUNGE—each thrust an exploration of traction. How much torque will the Firestones put to the pavement? First one, then the second staging light flashes on. The tree blinks down. With a bellow of rage, the Boss catapults itself into the black night, tapering smaller and smaller into the distance in one defiant howl.

In the dark beyond, bright digits flash on: 10.76 seconds, 134.44 mph. The Camaro is dead, dispatched by a single stroke of the executioner. The Boss's backup run is quicker still: 10.55 at 135.05.

"This is like Holmes vs. Shavers in '79," Coletti muses. Ernie Shavers scored a knockdown in an early round, but Larry Holmes came back to win when the ref stopped the fight in the 11th. "Overcoming adversity—to my mind, that's the mark of a true champ."

Round Two, GingerMan Raceway: Staffer and ardent road racer Tony Swan

will be our designated driver today on this 1.9-mile ribbon of blacktop

draped over the gentle contours of western Michigan farm country.

Moss's test driver reports that the Camaro's oil pressure drops to zero in right turns, which is most of them. To save the motor, Swan will drive in fifth gear, using fourth only to exit crucial turns.

The black car flashes in the sun, visible most of the way around the

circuit, as the big three-inch exhausts play fortissimo, then pianissimo,

at the direction of maestro Swan's right foot. We hear mild axle hop under

hard braking—something we've found in the street Camaros, too—but the laps

are otherwise uneventful.

As the Boss rumbles out of the pits, it seems the bettor's choice to sweep the match. With its solid horsepower advantage, viewed against the Camaro's handicap of fading oil pressure, it has Moss in the Rolaids mode today. Lap one looks good, quicker than the Camaro's first. Uh-oh, the sound went soft. Something wrong. From behind a crest the red Ford emerges, limping toward the pits.

Swan unbuckles. "Oil pressure's gone," he reports. The mechanics look at one another, remembering those fragments of steel they couldn't retrieve yesterday.

Ford vs. Chevy ends in a stalemate.

Afterword: It all seems casual, doesn't it? America's two biggest carmakers flexing their biceps before a friendly magazine. But Moss and Coletti didn't get to be generals by losing. Early in 1999, when the face-off began to look likely, the Boss had 720 horsepower. Not enough bullets, Coletti figured. An urgent dyno program lifted output "over 850." He thought he knew what Moss was packing, and that would cover it.

When the Camaro's hood came up in round one, he recognized the non-GM block. "Hey, Jon, whenja put in this Donovan?" Pure racing hardware. This wasn't the motor Moss had been showing around.

After the match, we asked the Tower about the "Donovan," how long it had been in the Camaro. He looked skyward, which is kind of a close-up for him, considering the possibilities. He allowed a slow smile. "About a month," he said.

"That a real number?" we asked, pointing to the hood scoop's 572.

"It's a real number."

"But is it the displacement?"

Again he considered. Again a smile. "Oh, about 580," he said.

Among poker players and street racers, that's full disclosure, as close

as you'll ever get.